“Long Bitcoin, short the bankers” is a rallying cry that seems all too familiar today. Of course, there’s many reasons to be excited about the potential for digital currencies: right now (mid 2019), a week seldom passes between the announcement of a promising new team, launched product or interesting milestone reverberating throughout the space.

But I fear that many of the things we are building today are the early versions - the ones that will look too finicky with time, or like overly optimistic and simplified versions of the eventual end state of this technology. Bill Gates clearly described the “Wallet PC” with built-in payment capabilities back in 1995 - far before Apple Pay became ubiquitous. PDAs were an early “Wallet PC” but seem deeply quaint, even compared to smartphones 5 or 10 years ago.

For crypto, the question is: have we reached the PDA stage yet? Or back in Apple’s (failed) Newton tablet and General Magic (another failed tablet) days? They were right, just too early.

If we look at the “job to be done” with privately issued monies, crypto today resembles the early days of banking (“Banking 1.0” if you will), more than most builders today might have ever considered. Here’s 4 lessons that crypto can learn from the rise of banking - that warrant close inspection as we think about the problems we are collectively trying to solve in this new technology epoch.

Some in the crypto community will quickly dismiss borrowing, bucketing it with desires for leverage or near-term liquidity. But there’s something more fundamental at work here: the role of credit in money supply (which interest rates inform).

Credit has many forms. Perhaps an overly used historical example: consider the Polynesian island of Yap. They used large stones - called Rai - as money. Sometimes too large to move, these limestone disks were left in place, in yards or for decorative uses, and ownership was maintained through oral record. Sometimes, the actual existence of the stone didn’t even matter. In one notable example, some Rai were lost to the bottom of the sea during transport (at no fault of the owner). These owners were allowed to continue to use and trade the Rai even though they were permanently lost.

Why? This is a system of credits. Physical settlement matters less - what’s important is allowing the coincidence of wants (“medium of exchange”) to take place. And whether it’s money on a bank ledger, or a town’s communal understanding of ownership rights to stones under the sea, it is good enough for the job to be done.

The current fiat money credit markets are underpinned by the notion of a “yield curve” - how much someone will pay you to use your capital, over what period. When I was investing full time, I searched high and low for something that would naturally generate a crypto-native yield curve. Ideally, this curve would be created by real use. LIBOR (the London Inter-bank Offered Rate of interest) is the yardstick used in much of the government-issued currency world - I wanted to see what protocol, group or organization might own the same for crypto. One potential (if far-off) contender considered: if lightning network gets widely adopted, perhaps the transaction fees collected on top of value locked in channels will prove a “real” yield from owning BTC. (Other current entrants include Maker’s Dai, the team at Compound and others in the crypto borrowing space, BlockFi and Celsius to name a few.)

A more practical example of the credit vs. money debate: the (Philz) coffee I am drinking while writing this was purchased not with money, but with credit (via my personal relationship with American Express). Now a few money-related things made this easier:

The coffee was denominated in US dollars

I happen to “physically” settle up with American Express every month

But for all intents of the purchase, all that matters are i) that we agree on a price in units that we can (hopefully) rely on and ii) that my grantor of credit and I have a way to settle up on whatever interval is needed. (Why do I put “physically” in quotes above? Read on.)

Some in the crypto ecosystem are asking why we, as a community, haven’t done a better job actually getting crypto accepted. In major countries with stable financial systems, I argue - the medium of exchange use case isn’t actually the job to be done here. The major credit card networks make it easy to transact - and while 3% fee feels high, to be able to transact seamlessly everywhere tends to be more valuable (event to merchants, vs forcing customers to use less-expensive payment methods) than this cost. For these nations, maybe the question we instead should ask is: when will American Express accept our “settling up” in cryptocurrencies?

But elsewhere in the world - where these networks aren’t as robust, inexpensive, or reliable - it’s much easier to see how the privately issued monies will make inroads. In Ingham’s The Nature of Money, there’s a delightful exchange at a cafe during the Argentine crisis at the turn of the 21st century. Two cafe patrons, after drinking their coffees, ask the waiter “how shall we pay?” This was a real question to settle. During the hyperinflation and failure of the Argentine government-issued currency in the early 2000’s, many alternatives had cropped up: USD, special monies to be used within shopping malls, and many varieties of company/bank/institution issued IOUs.

But private IOUs are really just…credit. Given to the holder of the note. With a promise of future payment.

So, we’ve been issuing decentralized “monies” for quite some time, long before crypto, using credit - only they’ve tended to be pegged to some standardized value accepted at that time and place (like USD or Rais)

Before we go gallivanting into the decentralized world, it’s worth taking a look at how we got to the current state of financial affairs — the current epoch of the twin horsemen of the central and commercial banks.

Just as we historically have had no problem using Rai, gold, or other kinds of commodities as money (see Thai government trying to buy fighter planes with 80,000 tons of frozen chickens) - it seems curious that we’ve landed on the current system.

It’s worth taking a look at what “job to be done” the current system is solving. In a commodity-as-capital dominated world, there was a major problem: credit was hard to come by. Pre-banking, the only source of borrowing was surplus capital holders: the robber barons of their day. These capital holders would weigh each lending opportunity against all the others - there was an actual opportunity cost to marking any given loan. Thus the “winning” projects (i.e. those willing or able to pay the most), might wind up with usurious rates of interest.

It’s worth noting almost every major religion has some decree prohibiting usury, because of the problems it causes. Of course, this was eventually softened with the passage of time - see the Medici family’s attempted atonement for their lending.

The point is: the banking system was initially created to route around surplus capital owners’ excessive rent-seeking. The banking system itself was an early network…and networks route around obstruction. Pre-regulation, it was a pretty simple proposition:

I (the bank) take pooled deposits from many people

I build myself a fancy building with lots of stone and pillars (so you know I’m not running away overnight with your money)

I then lend to anyone who I think will be able to pay it back…not necessarily the highest total rate of return (like the robber barons), because I have plenty of money from pooling a community’s deposits

I blend the rate of return across my deposit base — some good loans, some great loans, a default or two

I issue “banknotes” valid for money held within my reserves

As it turned out, this system worked pretty great for the time. Keynes noted that at its best, credit should be difficult to obtain, but inexpensive. That way, credit gets routed to the projects that are best able to put it to productive use (and can actually can repay it later, making society wealthier as a whole.) Credit for the sake of speculation and the value destruction from the compounding cost of overly unproductive interest rates (vs the linear rate of the real-world uses that will repay the loan someday) are topics deserving further inspection at a later date.

Of course, there’s a bit of a catch here - this works great until it doesn’t. If I, the bank, lend to too many disastrous or illiquid projects, I risk a run on the bank and the chance of colossal failure. How should you value a dollar guarantee from a bank you don’t know, far away in a distant city? Credit guides of the day (nowadays think S&P, Moody’s, etc) would value these banknotes. For example, the early banks of the “west” (then Illinois) were more susceptible to collapse, so their banknotes might trade at 50, 60 cents on the dollar all the way in Philadelphia.

Banks gave financial access to those under-served by the existing system. Providing borrowing for projects that could increase societal wellbeing was one major job to be done. Providing a better means of exchange than raw commodities was another - many banknotes was still better than assaying gold for every transaction, even with the perils of many note issuers. By taking the robber barons out of the loop, commerce could prosper.

Today, crypto ideals seek to do much of the same: route around obstructive third parties and increase the number of people and communities we can serve with the power of “finance.” It’s just not the first time a new system has been built with this goal in mind.

There are a number of steps that got us from a world of many different banknotes, each separately traded and evaluated, to today’s commonly accepted standard of a single fiat currency issued by a central bank. A few that I’d highlight (great reading on their own for the curious):

10% tax during the Civil War on State-issued banknotes vs. the Federal issued currency

Creation of the Federal Reserve itself in 1913

World War I reparations (all the gold ended up in the USA, causing liquidity problems world-wide, and temporary suspension of gold standard in Europe)

Creation of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) - a somewhat secretive organization acting as a central bank for central banks

Creation of the FDIC insurance on deposits during 1933 (and gold for dollars exchange)

Bretton Woods agreement and pegging of currencies world wide

And of course…1970’s abandonment of the gold standard

If I had to summarize key points from my study to date, I’d highlight the following:

Banks blowing up are bad for business (and the economy, thus tax revenues)

If each bank must hold its own gold reserves, we can still have liquidity problems (during times of high need for capital - e.g. around the time of crop harvest)

If we create a “bank for banks” than we can pool the pooled deposits, and add stability

Thus i) Federal Reserve holds the gold ii) banks have reserves and borrowing ability with the Federal Reserve iii) increased depositor confidence in banks leads to iv) stability within the system Add enough regulation on how much reserves a bank must have, forbid overly speculative lending practices, and soon enough you have bank adherence to the 3–6–3 rule:

“Borrow at 3%, lend at 6%, be on the golf course by 3 PM.“

But in this process of seeking stability, we’ve introduced a new power to the state: seigniorage.

For all the control that the central banks have, there’s a far more curious way that money gets created into the system: most money is created by commercial banks. Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, has dubbed this the fundamental “Alchemy of Money.” (And he’s written a delightful book of the same name.)

How do banks create money supply?

You deposit $1M USD into a bank account

I borrow $1M USD in a mortgage to buy a condo

I pay the owner of the condo $1M USD

That’s it. Now you and the seller of the condo both still have $1M a piece. The pooling of deposits (presumably this bank also has other people’s capital) enables the time-transformation of money. In a quick update of a database somewhere, we’ve created $1M out of thin air - or perhaps the future.

What’s important to note here: without extreme control of the banking system, the central bank doesn’t have control of the total monetary supply. It can lower rates to inspire more lending, but that doesn’t mean that banks will lend at those rates. Deregulation proponents say that government shouldn’t decide who or how credit is extended - but in the case of FDIC-insured institutions, the government (translate: us, the taxpayers) are on the hook for any moral hazards. (Want vivid examples of this? See the systematic looting of US Savings and Loan institutions in the 1980s.)

So even if the Fed were to keep control of its budgets and do its best to maintain small, tractable inflation to promote stability, commercial banks can run amuck with what we know as as “dollar.” This is before trillions of quantitative easing (QE) and other “benefits” of printing the money (seigniorage) that the Fed is afforded.

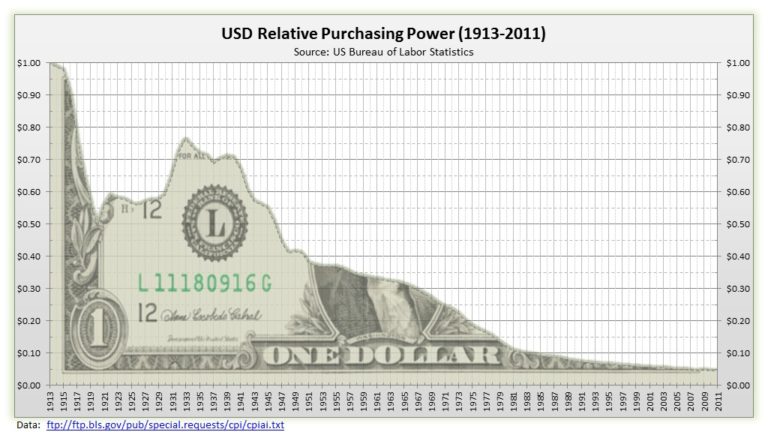

Even if its true value is in decline (see figure above), it’s clear that the strength of the US Dollar has given the US an incredible advantage in the world markets. For instance, consider the ability, for both corporations and the government, to borrow in our own currency from other nations.

This might seem like just a matter of accounting, but many nations’ currencies have been crushed when they have have accumulated too much debt denominated in someone else’s currency. As an example - say the Argentine government has a $100M USD obligation. They can print more of their own currency to fill the obligations, but this will drive down the exchange rate of their own currency, further increasing the “real” cost of the interest (and further exacerbating their difficulty repaying.) So trust (ability to borrow) in the USD is a huge boon. This trust, it turns out, is pretty wide spread - by the IMF’s estimates, foreign nations hold 62% of the their reserves in USD.

Remember when I said above that American Express and I “physically” settle each month? It’s not that simple: we exchange virtual IOUs between banks, that are themselves virtual IOUs from the Fed, which itself an IOU from the US Government, denominated in something that, in real terms, is eroding in value. And all this is without choice or alternatives.

I’m lucky; my needs are in USD, and tend to be focused in a limited geographic area. But the world (and my business) is far larger and more complicated. We pay our suppliers in 167 countries (everywhere allowed by OFAC), with minimal transaction fees or costs.

Bitcoin enables a truly limited money supply, similar to gold’s physical scarcity. But lending - and other currency issuance and forking of existing chains - may well create most of the money supply in crypto. Rather than being concentrated to only nation issuers, the benefits of issuing currencies will be more widely distributed than has ever been possible.

~

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme sometimes. We’ve seen parts of this movie play out before - and while we are always looking ahead to the future, there’s lessons to be learned from the network builders before us.

If you enjoyed reading this (or just read this far), subscribe for future posts below. Thanks to Kevin Kwok and Jason Comerchero for reading drafts of this.